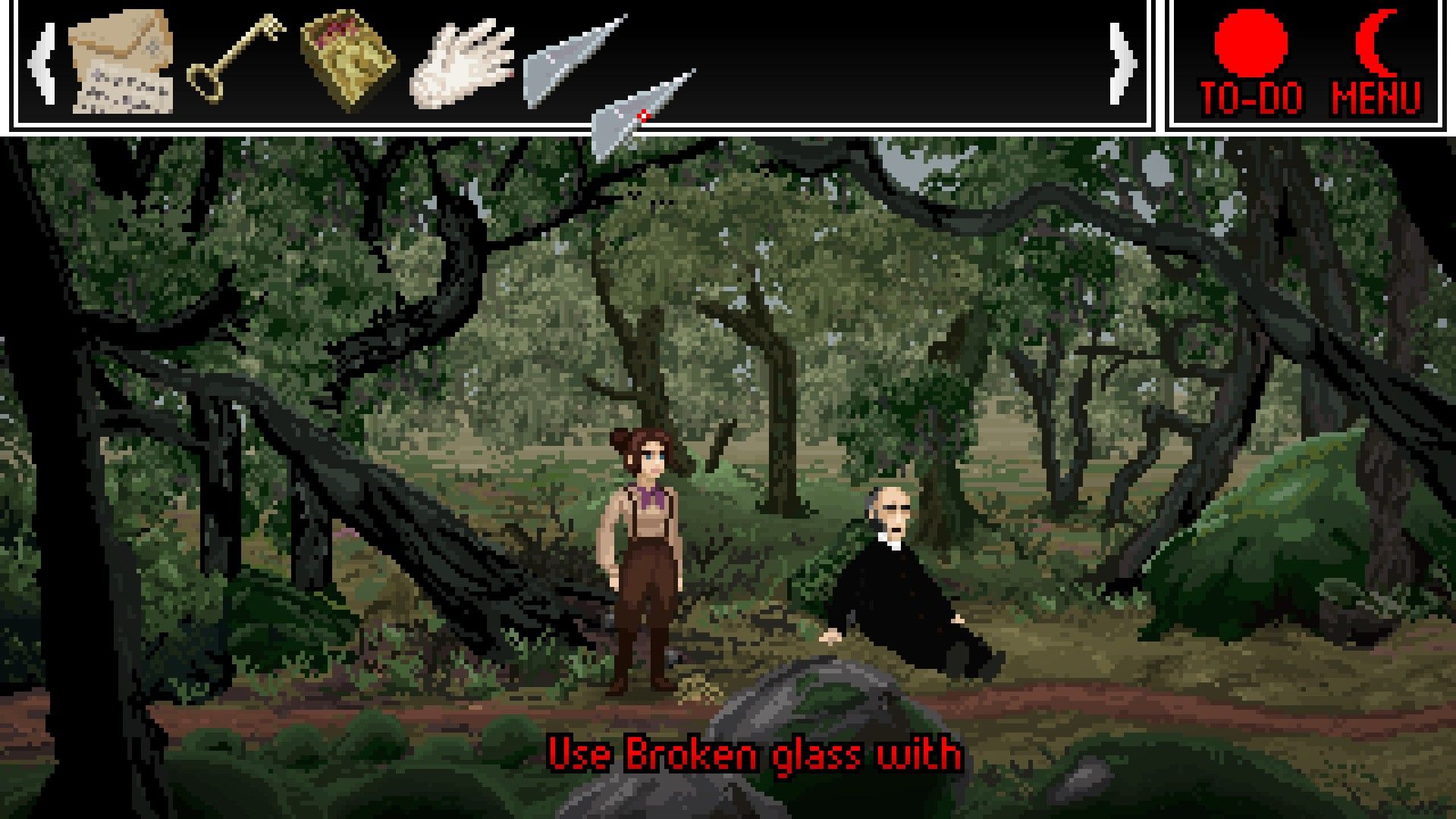

This looming dread, growing increasingly loom as the game goes on, is one of the most effective weapons in Hob’s Barrows’ arsenal of horror. Thomasina, a barrow-digger and proto-feminist trouser-wearer in a time when trousers were worn by men, is a practical and mostly cheerful woman. She approaches all the puzzles she has to solve in the robust, roll-your-sleeves up manner of an old-timey governess who doesn’t care if you hate learning French verbs. The Thomasina of the future voiceover, however, sounds blank, drained and sad. It’s a contrast that weighs more and more heavy as you slice into the horrible heart of Hob’s Barrow, and it underscores how great it is to play the game in its fully voiced form. As well as the voice acting, Hob’s Barrow has an appropriately creepsome soundtrack, making fabulous use of the juddering bass tones that put all humans and related monkeys automatically on edge, and isn’t a stranger to unsettling lighting. Evil in this game is a sick purple. Most of all, some praise should be especially given to the several horrible close-ups that pop up: Thomasina’s eyes, wide in shock, a malevolent cat as he crawls onto your bed; round eyes over a slack, downturned mouth with little peg teeth in it. Devs Cloak And Dagger Games can coax extraordinary depth and motion from their pixel-art and then use that to repulse you. Thomasina isn’t just running around bumping into spooky things at random, though. She’s in the isolated hamlet of Bewlay, near Bakewell, because a local wrote to her to tell her about Hob’s Barrow, a prehistoric burial mound nearby ripe for the excavatin’. Except, when Thomasina arrives, there’s no sign of the man who wrote to her, and all the other locals (almost all of whom are various flavours and levels of dour) insist they haven’t heard of any such barrow, what even is a barrow, who’s asking anyhow? Without money, contacts, or the full picture, you have to engage in some point and click puzzling, first to find the barrow and thence to get inside the bloody thing. It takes Thomasina about a week, during which time things get increasingly eldritch, and flashbacks to her childhood are woven in. The puzzles themselves are alright (I only got properly stuck once, right near the end, and it was because I was being silly) and pretty logical, but encourage a slightly sideways angle on the logic. One solution needs you to make a poultice to treat arthritis, so an old man can milk his goat. Others are easier if you already know where fairies live, or what a horse’s favourite treat is. There’s always a visible ladder between them. You can see most of the rungs further up at “get this woman some goat’s milk”, back down to where you are, which is at “cannot milk goat”, and know that you need to go via “steal produce from uninvolved market seller”. It’s just a case of figuring out the gaps, and honestly, it probably won’t take you that long. Hob’s Barrow uses the expected streamlined point and click controls to make things easier (you can highlight all interactable items in a scene, there’s a mouse-over inventory at the top, and you click and drag to use an item on something else), and all told you’re probably looking at around four hours to unleash terrible eldritch forces that should be left well alone. Not a bad afternoon’s work. I think I was more impressed by how the puzzles themselves harmonise with the rest of the game. They’re country puzzles, folky puzzles - all stone and mud and wiggling worms - that get less normal and more hands-on and weird in time with Thomasina getting more enveloped in the strange, mythic power of Bewlay and its moors. The Excavation Of Hob’s Barrow does a good job of creating a sense that the landscape itself is somewhat hostile, and that you’re up against something almost the size of the moor itself, a battle represented by the people in Bewlay. Both you and Thomasina are first repelled by and then grow used to the locals. There are definitely two factions visible - two schools of thought - but over the week Thomasina spends in Bewlay she gets to know them, and they become less strange. The first time you meet the vicar he vomits and nearly faints, but you become familiar with him and the church and almost forget that the sicking-up incident ever happened. You have a couple of drinks at the local. You get to know your way around, so you don’t get lost, and can instead focus on the strange, bleak beauty of the place - in rain, in mist, at night. And Thomasina starts to believe the portentous and horrible dream she had on her second night. The trouble is, she believes it’ll lead to something good, but you know that it will very much turn out bad - and you know because future Thomasina keeps telling you. When the charming local lord turns up he has “I am a smiling villain!” practically tattooed on his forehead. A surprising link to Thomasina’s father is clearly extremely bad, not good. You are at odds with the Thomasina exploring Bewlay, player knowledge and character knowledge diverging in a way that enhances the game, because every step forward gives you the same feeling as Randy in Scream trying to explain the rules of horror movies to everyone else. I still solved all the puzzles because surely at some point there’d be a puzzle that averted disaster for Thomasina. But this is a beautifully dank, damp, gloomy folk horror. There’s no way to save Thomasina. But you’ll try, anyway.