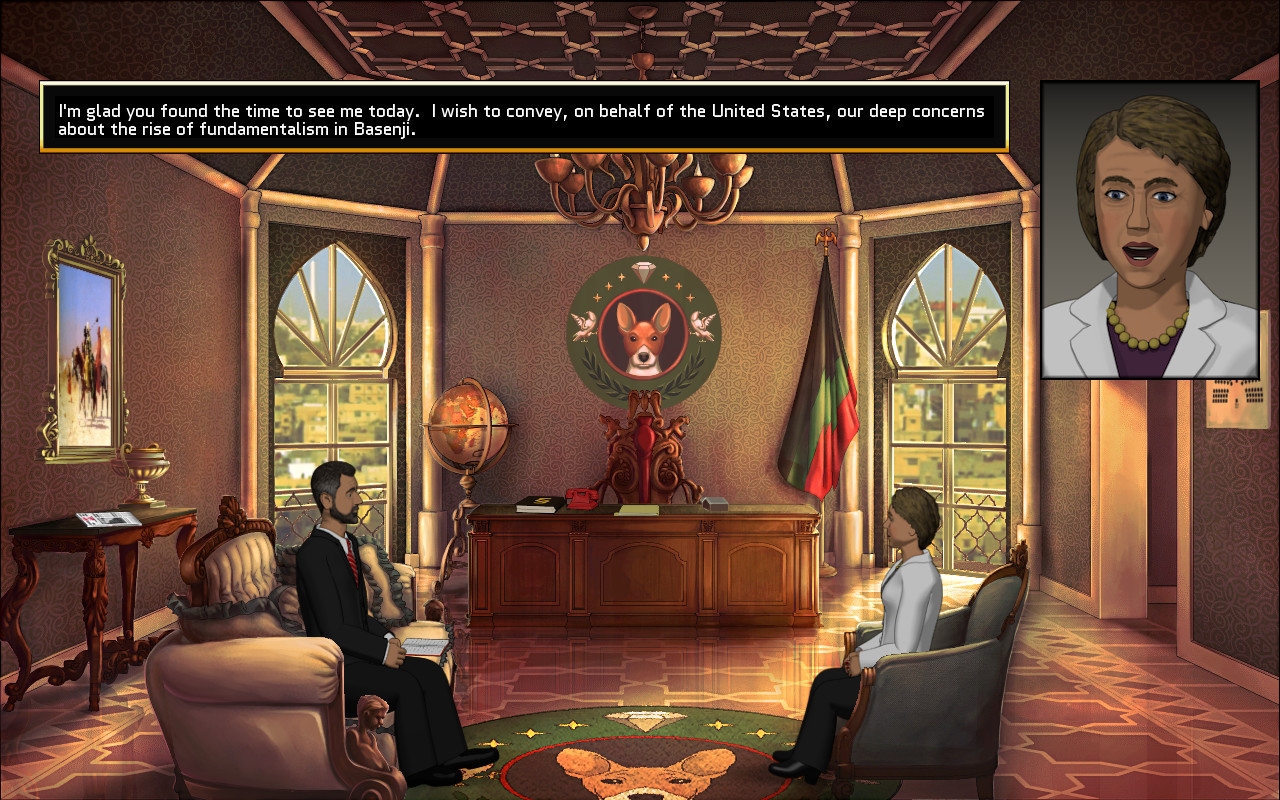

Ryan is currently putting the finishing touches to Rogue State: Revolution, a souk-lively Middle Eastern nation-building sim happy to tackle issues most games wouldn’t touch with a ten foot barge-pole. As I discovered during an absorbing morning with the eighteen-turn/month press demo, there are few easy answers, few win-win situations, in post-revolution democratic Basenji.

RPS: Before we talk about Rogue State: Revolution, would you describe your unusual route into game development? Ryan: Like a lot of my favorite people, I didn’t start in game development. I worked in nuclear safeguards for Canada’s nuclear regulatory agency for a few years, then later served as a policy specialist in nuclear counterproliferation. I dabbled in diplomacy, and was deputy director for Canada’s bilateral relationships in the Gulf region for a year or so, before leaving the public service, emigrating to the United States and starting a new career as a teacher while simultaneously building a small indie studio with Little Red Dog Games. I’ve since gone from teaching American history to middle-schoolers to teaching game design and development to college students. LRDG has changed a fair bit too as we’re now able to take on larger, more ambitious products than ever before.

RPS: When you hear RSR described as a “Civ-like” how do you feel? Ryan: We take it as a compliment. It is certainly a good pedigree to be associated with, though I don’t think that’s quite what players should be expecting. There are a great many things to construct, and policies to adopt, and units to build to defend your territory, but the focus of the game is and always has been on keeping your political cabinet happy lest they start obstructing your government rather than supporting it.

The economy of RSR behaves fairly differently from what you would expect from a Civ-like game as well, where the majority of your income will come from the consumption of your state-run subsidies rather than a tax base.

RPS: Just how bad can things get during games? Are Syria-style multi-faction civil wars possible? Ryan: Bad wears many hats in RSR. There is a single unified enemy faction within your nation, and that is the Basenji Liberation Front: an organized group of insurgents who oppose your policies, whatever they may be. That faction may be bolstered by nations who would benefit from seeing your democracy fail. There are also three neighbouring nations who choose to invade if you are unable to maintain a secure border and an amicable relationship. There is also a separate marginalized group of people seeking total political autonomy from your nation which you can grant or ignore at your peril. There is also the threat of desertification, economic collapse, food scarcity, invasive species, the rise of a sentient AI, invasion from a superpower or being struck by a meteor the size of a football field. This is a game where pretty much anything can happen.

RPS: My last interviewee, Dan Dimitrescu of KillHouse Games, recommended that devs shouldn’t tackle sequels straight away. Are you glad you didn’t embark on RSR the moment Rogue State* shipped?

- pictured above Ryan: So glad! We always knew we wanted to revisit Basenji, but needed time to pivot to a new engine, build a stronger team and make a lot of the kinds of mistakes that are expected in indie gamedev before it could happen. If we rushed into it, the product would be more of an update than a meaningfully real sequel. We had to grow up and make different kinds of products before going back to our roots and finding the fun in RS. Our lead programmer, Denis Comtesse, and I have been working as a team for eight years now, which probably outlasts a lot of marriages out there. That’s eight years of experience playing to each other’s strengths, figuring out how to push for a “yes”, accept a “no”, and figure out how to make this product live up to its potential. This is our first game that we can point to and say, “This is exactly how we wanted it to be.” and we’re incredibly grateful to our publisher for believing in us as much as the game itself.

RPS: From a coding perspective, which aspects of the game have proved the most challenging? Ryan: There were a few tough ones. Taming the procedural map generation comes to mind. Writing some code that generates a random map is easy, generating provinces, towns, road connections, that’s all well and good. Making sure that the map is never unplayable, essential parts can never be disconnected, that nothing breaks the gameplay and all potential edge-cases are taken into account, while still keeping things random enough? That took an insane amount of tweaking and debugging. Our associate programmer, Nick Colucci, has built unit-movement algorithms that appear simple but do a lot of very complex things under the surface that give us all a newfound respect for other games in the genre.

RPS: How would you define a “rogue state”? Ryan: The term is getting thrown around a lot these days, particularly both by and against the United States, to the point where the meaning is purely contextual. Personally, I prefer to reserve the term for describing countries whose everyday conduct is erratic and often undiplomatic. I’ve sat in on many very tedious speeches at UN organizations in the past as one-by-one every nation in the world stands and deliver twenty-minutes or more of expected platitudes and reports. But every so often you get a speech delivered from a country that one might characterize as a “rogue state” that is so hostile or off-topic that it can be hard to suppress a giggle. Reminiscent of a high-schooler who didn’t do the book report but is going for broke presenting something bizarre and random because they simply do not care for the class or its expectations. So too do we expect the rogue state to surprise us, doing something free from the rules and structures imposed upon it by institutions it does not respect.

RPS: In RSR is it possible to develop or acquire nuclear weapons while maintaining cordial relations with superpowers like the USA? Ryan: Not exactly. There are two ways to acquire uranium for a civilian nuclear energy program: either from a trade deal with an allied major power (US, China or Russia) or by exploiting a discovered domestic supply. Once you have uranium coming into your production chain, you may choose to divert a small quantity of it to a clandestine site for further enrichment and later weaponization. You may get caught doing this, and then you face some options:

- Keep going and hope to secure a weapon of mass destruction before facing a focused strike on your clandestine facilities; or

- Renounce your nuclear weapons efforts, take the diplomatic hit, and embrace the roadmap to compliance with your nuclear non-proliferation obligations put before you by the International Atomic Energy Agency. There’s no way the superpowers will tolerate your violation of the NPT, but if you’re very careful, put the right people in charge, and follow the right policy tracks, they may not discover it until it is too late and then they will dare not do anything to stop you.

RPS: Is there a danger in setting a game in a fictional state that you end up homogenizing or caricaturing Middle Eastern countries? Ryan: There is always a danger of the game being received in a manner that we did not intend, but one of our paramount design goals is to highlight that the Middle East hosts a mix of diverse values and interests that would be just as familiar as if the game was set in any other nation. As far as homogenizing goes, we want to challenge the perception of the region by the West as monocultural in Western political discourse, education and characterization in the media. There is a vast difference between life and society in Jordan and Oman, and a wide spectrum of difference between the values of the citizens who live and work in either. With our game, we want to emphasize that all nations, democratic and otherwise, will inevitably have citizens whose desires are ignored by their governments and will be vocal about it.

Addressing the risk of caricaturization, one of our governing design principles is that the citizens who live in Basenji have reasonable needs that are shared by people who live anywhere else in the world. They are immediately relatable: they want their kids to do well in school, they want to be able to earn money, they care about the environment and they go to the doctor once a year. These people are effectively held hostage by a dysfunctioning government, something that people all over the world (except maybe New Zealand?) can relate to. As the person in charge, you are empowered to either take advantage of that dysfunction or take the steps that you believe are needed to correct it. Basenji is a fictional country in a strange alternate universe that does not stand-in for any real nation in particular, and in practice, it has as much in common with Sri Lanka or Nigeria as it does Saudi Arabia. We’ve received a lot of support from people in the region who approve of how things are characterized (rather than caricatured) and brought on a cultural consultant to help us ensure that we are subverting the expected tropes without losing our sense of humor. I hope we’ve struck the right balance.

RPS: If you could force RSR players to read one book about the game’s subject matter prior to playing, which book would it be? Ryan: Funnily enough, I recently finished The Idea of the Muslim World: A Global Intellectual History by Cemil Aydin. It’s a fairly academic read with an internationalist perspective but I want to believe a reader will see the influence on our game. And if you get a second book, I’d also like to strongly endorse City of Lies by Ramita Navai because I hope it gets optioned into a Netflix series.

RPS: You obviously follow Middle Eastern affairs pretty closely. Are there current stories that you feel should be getting more attention in the Western press? Ryan: While there are issues present in some nations in the region that I feel stand out, I’m going to resist calling attention to those and instead note that the most important issues in the region are the issues that also affect the whole world: How do we stop a global pandemic? How do we prepare for the next one? How do we address the effects of global climate change? How do we address the pressures that come with mass-migration? What hope can we leave for the new generation? The best stories that we should be focusing on are the stories that transcend borders. RPS: Thank you for your time.

Chancing upon a perfect Close Combat substitute the week after bewailing the lack of one would make great copy, but sadly The Battle of Rip Creek, although not short of endearing qualities, doesn’t qualify.

Released on Wednesday, Matthew Ferri’s £10 top-down near-future RTT feels more like CC’s forerunner than its latest iteration. Inaccessible buildings, shortish view ranges, and an extremely limited order palette compromise realism that solid AI coding and plausible ballistics work hard to nurture.

The demo showcases the game’s tense, unscripted firefights and unpredictable opponents pretty well. What it doesn’t do is give potential purchasers a taste of the natty Graviteam Tactics-style operation engine. In the full game between real-time scraps you move platoons around a strat map representing Rip Creek’s nine districts; forces can be rested and reorganised, fortifications constructed and off-map assets like artillery and recon aircraft assigned. It makes a nice change from a mission sequence.

Tracked “bots” equipped with rocket launchers are the game’s apex predators. Hunting these with your own trundlers and AT teams… smartly shifting an infantry section to avoid an incoming mortar stonk… seeding a smoke screen to enable a flanking manoeuvre… at times such as these The Battle of Rip Creek scratches the Close Combat itch surprisingly vigorously. It’s when you’re struggling to arrange grunts around a house that’s essentially a rectangular boulder, or wondering how, on open ground, an enemy bot could have got so close without being spotted, that the lustre dulls somewhat.

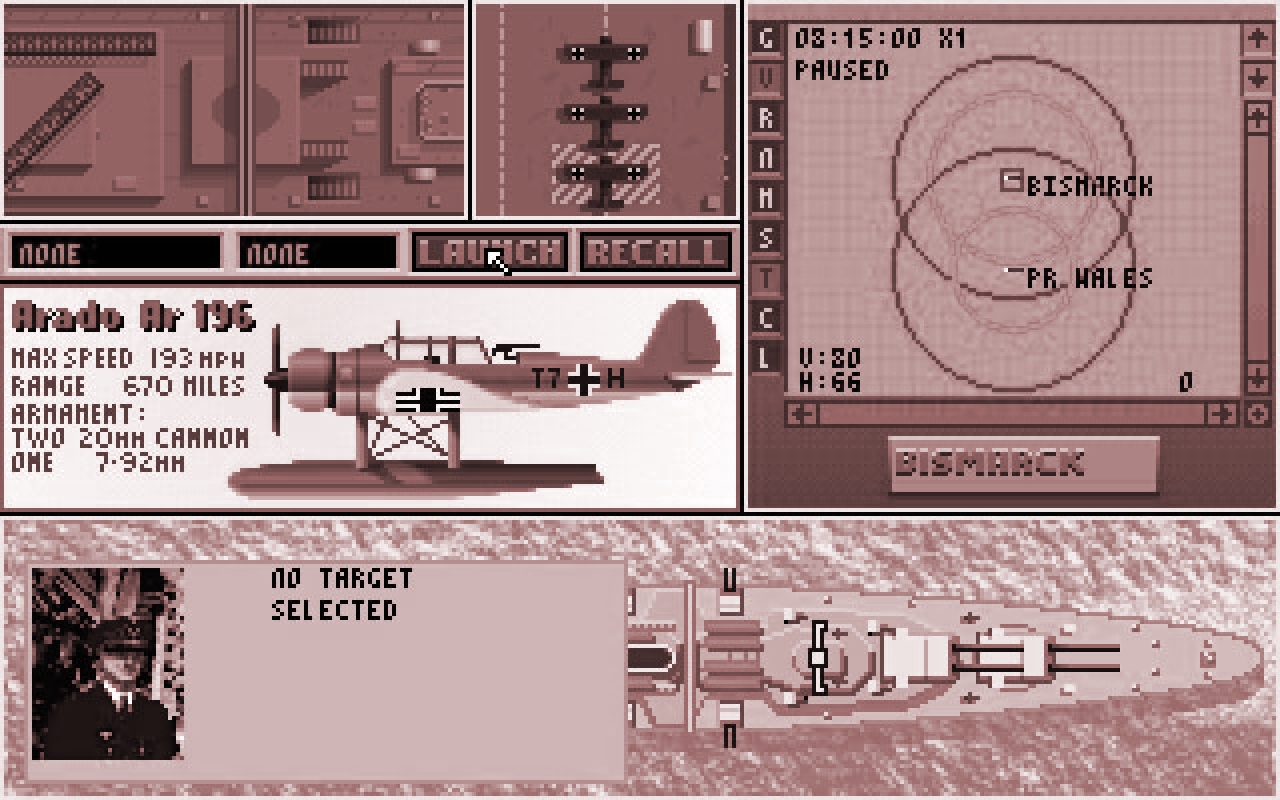

With less than a week to go to the submission deadline of the first Flare Path game jam, my coastwatchers in Sweden and Denmark tell me that the Baltic is crowded with Bismarcks under trial at present. Furious Lütjens and Lindemanns have been bawling at each other through megaphones. New paintwork has been scraped. Several nosy Arado Ar 196 floatplanes have returned home with flak-perforated flight surfaces.

While entrants test, tweak, toil and squabble I’ve been sourcing some splendid prizes. In addition to priceless publicity, one successful contestant will be receiving a lovely, lavishly-illustrated hardback about the short-lived battleship. The generous folk at Osprey Publishing have donated a copy of The Battleship Bismarck by Stefan Dramiński, the perfect reference tome if you decide to up-realism your design post jam.

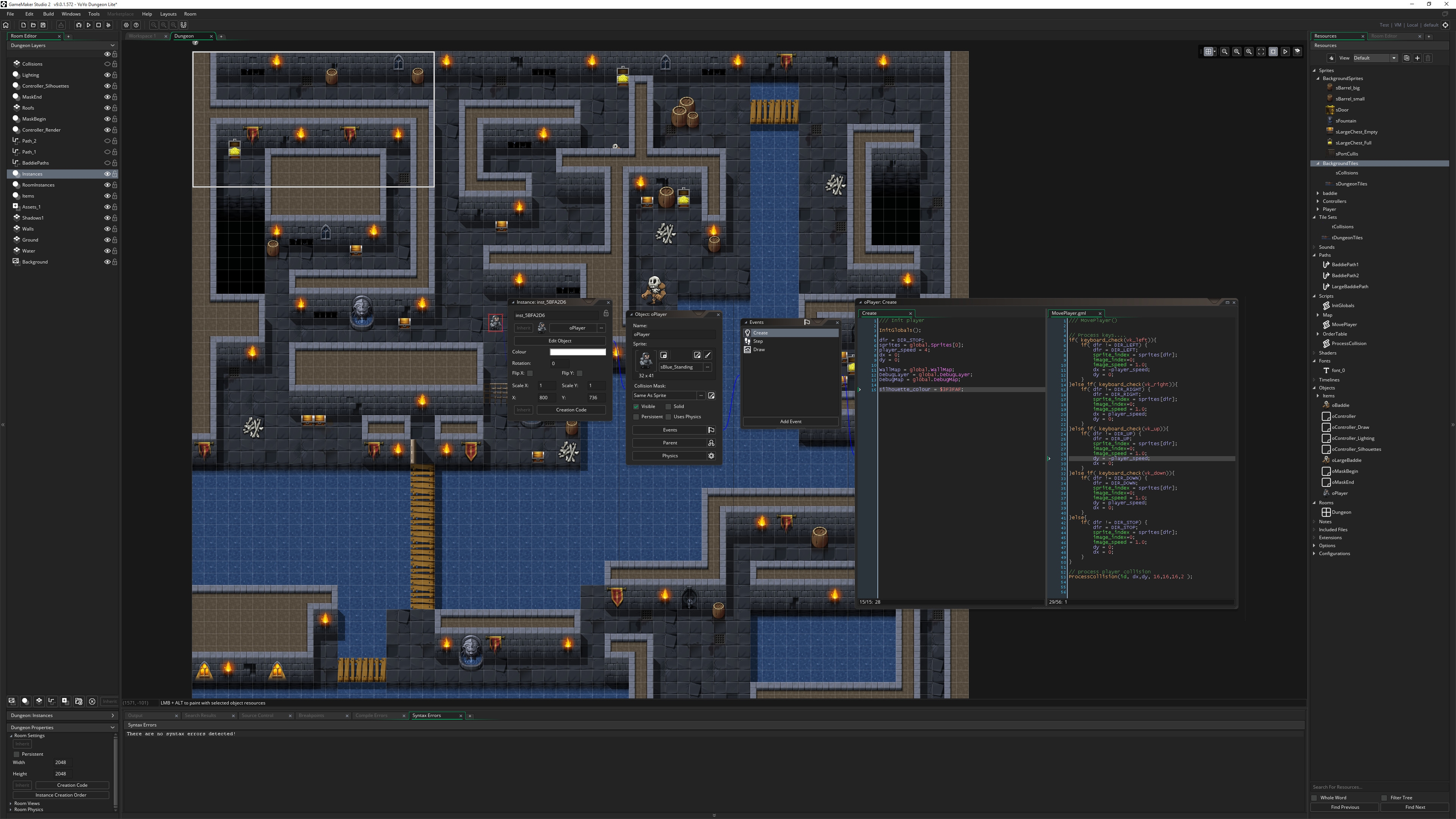

Thanks to YoYo Games’ munificence, the makers of the three best board game designs can expect to find activation codes for GameMaker Studio 2 in their inboxes after the results are announced. I’m speaking from personal experience when I say that GM makes crossing the Great Divide between cardboard wargame design and digital wargame design surprisingly easy.

To the foxer